Abstract art - Bozelos Panagiotis

Explore innovative architectural designs, trends, and insights. Join our community of architecture enthusiasts for tips, inspiration, and the latest news in the world of architecture. - Created by Bozelos Panagiotis

Wednesday, May 7, 2025

Elevating Education: A Guide to Designing Schools and Universities in Architecture

------

Elevating Education: A Guide to Designing Schools and Universities in Architecture

Understanding Educational Philosophy:

Flexibility and Adaptability:

Spatial Organization and Connectivity:

Sustainable Design and Environmental Quality:

Community Engagement and Collaboration:

Safety and Security:

Inclusivity and Accessibility:

Conclusion:

------------

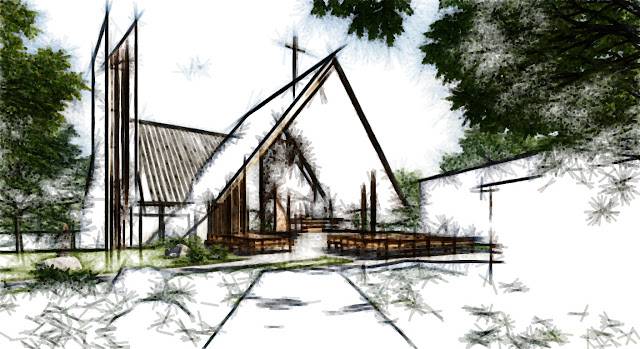

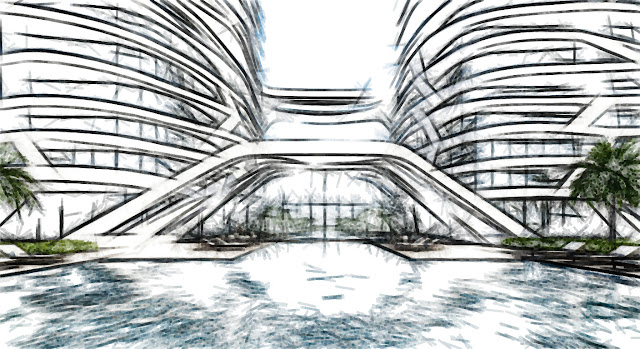

The sketches and basic renders I create are primarily intended to overcome creative blocks. They are abstract in nature and not final designs, often leaving room for multiple interpretations. For example, some sketches can be viewed both as elevations and floorplans, depending on how they are manipulated in space. These works are flexible and can be easily transformed by tweaking their geometry, adding modern facade systems, or incorporating other elements. An expert in the field can take these sketches, modify them, and further develop them into floorplans, sections, and elevations. Additionally, I also explore and publish my experiments with various AI image generators as part of my creative process.

I dedicate a significant amount of time each month to maintaining this blog—designing, publishing, and curating new content, including sketches and articles. This blog is entirely free and ad-free, and I plan to keep it that way. As I manage it independently, without any staff, your support truly makes a difference.

If this blog has helped streamline your work, sparked new ideas, or inspired your creativity, I kindly ask you to consider contributing to its ongoing upkeep through a donation. Your support enables me to continue providing high-quality, valuable content.

All sketches and artwork featured on this blog and my Pinterest pages are available for purchase or licensing, subject to my approval.

LINKEDIN PROFILE: https://www.linkedin.com/in/panagiotis-bozelos-96b896240

CV : https://drive.google.com/file/d/1mKd0tFYFREnN1mbsT0t42uOavFln4UOo/view?usp=sharing

BLOG: www.architectsketch.blogspot.com

PINTEREST (sketches): https://gr.pinterest.com/bozelos/sketches-and-plans/

Don't hessitate to communicate with me for anything you want.

Contact info:

bozpan13@gmail.com

bozpan@protonmail.com

TEL: 00306945176396

DONATE ME : Donate to Panagiotis Bozelos

---------------------------

Tuesday, May 6, 2025

AI in Architecture: Will Robots Replace Human Designers?

AI in Architecture: Will Robots Replace Human Designers?

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming industries across the globe, and architecture is no exception. With algorithms now capable of generating floor plans, optimizing structures, and even suggesting aesthetic improvements, many are beginning to ask a provocative question: Will AI replace human architects?

The answer, as with most things in architecture, lies not in absolutes but in balance. AI is reshaping the architectural process — but rather than replacing human designers, it may ultimately redefine what it means to be one.

The Rise of AI in Architecture

AI technologies are already integrated into multiple phases of the architectural workflow:

-

Generative Design: AI tools like Autodesk's Generative Design or Spacemaker use algorithms to explore thousands of design options based on input parameters such as light exposure, ventilation, materials, or spatial efficiency.

-

BIM (Building Information Modeling): AI enhances BIM platforms by detecting design clashes, predicting construction timelines, and automating repetitive tasks.

-

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability: AI analyzes building performance data to recommend solutions for minimizing energy consumption, maximizing solar gain, or choosing optimal materials.

-

Urban Planning: AI can simulate traffic flow, population density, and environmental impact, helping architects design smarter cities.

-

Design Visualization: AI-driven tools like DALL·E or Midjourney can create realistic renderings, suggest visual styles, or even propose conceptual designs in seconds.

These capabilities are not hypothetical — they’re being used today. But do they truly design? Or do they assist?

The Human Element: What AI Can’t (Yet) Do

While AI excels at optimization, pattern recognition, and simulation, it still lacks many of the qualities central to human creativity and architectural meaning:

1. Intuition and Ambiguity

Architecture often deals with ambiguity, intuition, and cultural symbolism — areas where AI struggles. A human architect can design a museum that not only functions efficiently but also provokes emotion, reflects history, or challenges social norms.

2. Contextual Sensitivity

Understanding the unique character of a place — its cultural, social, and emotional resonance — requires lived experience, empathy, and subjective judgment. AI can analyze data about a city, but it cannot yet feel the atmosphere of a street.

3. Ethics and Social Responsibility

Architects must often make ethical decisions: who benefits from this project? Is it inclusive? Does it displace communities? These are moral considerations, not just technical ones — and they require human values.

4. Collaboration and Vision

Architects work with clients, engineers, artists, and communities. They mediate between visions, lead creative processes, and bring ideas to life through dialogue. AI can support this process but cannot replace its social and emotional core.

Architects + AI: A New Creative Partnership

Instead of viewing AI as a rival, many forward-thinking architects see it as a creative collaborator. By automating time-consuming tasks (e.g., drafting, cost calculations, compliance checks), AI frees up architects to focus on higher-order thinking — concept, storytelling, and innovation.

Firms like Zaha Hadid Architects and BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) are already experimenting with AI-driven design processes, blending human intuition with machine-generated insights. AI becomes a kind of “co-designer,” offering alternative options that a human might not consider, while still allowing the architect to curate and lead the final vision.

In this hybrid model, the architect becomes more like a conductor — orchestrating inputs from humans, machines, and the environment into a meaningful whole.

The Future of the Architect

As AI grows more capable, the architect's role may evolve in surprising ways:

-

From Draftsman to Strategist: Architects will focus less on drawing and more on problem-solving and conceptual thinking.

-

From Solo Designer to Facilitator: With AI and data specialists on the team, the architect may take on a broader role, managing cross-disciplinary collaboration.

-

From Creator to Curator: Rather than designing every detail, architects might choose, edit, and assemble options produced by intelligent systems.

Ultimately, the core question isn’t whether AI will change architecture, but how we choose to use it. Will it be a tool of efficiency only, or a new medium for human expression?

Conclusion: The Architect Enhanced, Not Replaced

AI is not the death of the human architect — it is the evolution of architectural practice. Like the pencil, the CAD program, or the 3D printer, AI is a tool — powerful, yes, but still requiring human vision, ethics, and emotion to guide it.

Robots may generate plans, but only humans can generate meaning. As long as architecture aspires to serve human life in all its richness, the human touch will remain essential.

The future, it seems, is not man versus machine, but man with machine — building together.

Sunday, May 4, 2025

Beyond Aesthetics: The Philosophy of Functionalist Architecture

Beyond Aesthetics: The Philosophy of Functionalist Architecture

Architecture has long walked the line between utility and beauty — between serving human needs and expressing cultural aspirations. But in the early 20th century, a powerful architectural philosophy emerged that radically redefined this balance: functionalism. More than a stylistic movement, functionalist architecture is grounded in a belief that form must follow function — that buildings should be designed based on purpose, not ornamentation. At its core, functionalism is not just about how buildings look, but about what they do — and why.

What Is Functionalist Architecture?

Functionalist architecture is guided by the principle that every element of a building should serve a specific purpose. Rather than adorning structures with decorative features, functionalism emphasizes clarity, simplicity, and rational design. The building becomes a tool — streamlined, efficient, and often minimalist — meant to enhance the activities it contains.

This philosophy was a response to the excesses of 19th-century historicism and the ornamental overload of styles like Art Nouveau. In its place, functionalism brought a new ideal: architecture as a reflection of modern life, industry, and reason.

Origins and Key Thinkers

Functionalism’s roots lie in the industrial and social upheavals of the early 1900s. As cities expanded and populations grew, there was a pressing need for affordable housing, efficient infrastructure, and buildings that could meet the demands of a changing society.

Influential figures like Louis Sullivan, often credited with the phrase “form follows function,” laid the philosophical groundwork in the United States. Meanwhile, in Europe, the Bauhaus school in Germany — led by Walter Gropius — and architects like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe pioneered functionalist designs that rejected the past and embraced a new, machine-age aesthetic.

Their buildings often featured flat roofs, open floor plans, geometric forms, and a lack of ornamentation — not out of artistic restraint, but in pursuit of clarity and purpose.

The Core Philosophy: Utility as Meaning

Functionalist architecture is underpinned by several philosophical ideas:

1. Truth to Materials

Materials should be used honestly and visibly. Steel, glass, and concrete are not hidden or masked — they are celebrated. This transparency reflects an ethical stance: design should not deceive.

2. Form Reflects Purpose

Rather than designing first and adapting later, the function of a building determines its shape and structure from the start. A school, a factory, or a home should each have a distinct architectural language derived from its use.

3. Minimalism as Clarity

By stripping away the superfluous, functionalist architecture aims for purity and precision. The result is not emptiness, but focus — an environment where every detail has a reason to exist.

4. Democracy and Equality

Many functionalists saw their work as a path to social progress. Housing that was affordable, hygienic, and efficient could elevate the lives of ordinary people. Architecture, in this view, was a social mission — not just an artistic pursuit.

Criticism and Evolution

Despite its noble aims, functionalism has not been without criticism. Opponents argue that its emphasis on utility sometimes led to cold, impersonal buildings that ignored emotional resonance and cultural context. The starkness of mid-20th century modernism — with its concrete towers and sterile housing blocks — often failed to inspire the human spirit.

In response, the late 20th century saw the rise of postmodernism, which reintroduced symbolism, playfulness, and historical reference into design.

Yet even as architectural tastes shifted, functionalist principles quietly endured. Today, they influence green building standards, modular construction, and user-centered design. In many ways, the digital age — with its love for clean interfaces and optimized systems — echoes the functionalist ethos.

Functionalism Today: A Living Philosophy

Modern functionalism is no longer confined to stark modernist forms. It now lives in sustainable design, adaptive reuse, accessible architecture, and context-sensitive planning. Architects are blending function with feeling, purpose with poetry. Buildings are being designed not only for what they do, but for how they make people feel — efficient and emotionally intelligent.

Take, for example, libraries that double as community hubs, hospitals designed for healing beyond treatment, or urban housing that fosters neighborly interaction. Here, function is no longer opposed to aesthetics — it includes it.

Conclusion: The Soul of Function

Functionalist architecture reminds us that beauty is not only skin-deep — it can emerge from integrity, purpose, and clarity. When design is honest, efficient, and responsive to human needs, it transcends mere appearance. It becomes philosophy in form.

In a world increasingly defined by complexity and noise, functionalism continues to offer a radical idea: that simplicity, when rooted in purpose, can be both elegant and profound. And that, perhaps, is the truest form of beauty.

Saturday, May 3, 2025

The Return of Human-Centric Design: How Architecture is Prioritizing Well-Being

The Return of Human-Centric Design: How Architecture is Prioritizing Well-Being

In recent years, a powerful shift has been underway in the world of architecture and urban planning — a movement that places human well-being at the core of design. After decades of prioritizing efficiency, profit, and spectacle, architects and developers are now rediscovering the essential truth: buildings and spaces exist for people. This resurgence of human-centric design is redefining how we shape our environments, emphasizing comfort, connection, health, and meaning.

The Roots of Human-Centric Design

Human-centric design is not a new concept. Ancient civilizations intuitively built spaces that responded to climate, community, and cultural needs. From the agora in ancient Greece to the shaded courtyards of Islamic architecture, spaces were designed to nurture social interaction, spiritual life, and physical comfort.

However, the rise of modernism in the 20th century brought a mechanistic and often impersonal approach. Skyscrapers, concrete monoliths, and sterile office blocks prioritized form over feeling. The human scale was often lost amid grids, glass, and industrial repetition. As a result, many environments began to feel alienating, unhealthy, and disconnected from nature.

The New Paradigm: Designing for Well-Being

Today, architects are once again turning toward designs that serve the full spectrum of human needs — physical, emotional, psychological, and social. This new wave of human-centric architecture focuses on several core principles:

1. Biophilic Design

Nature is essential to human health and happiness. Biophilic design integrates natural elements — sunlight, greenery, water, and organic materials — into built environments. Studies show that exposure to nature can reduce stress, improve cognitive function, and promote healing. Buildings with green walls, indoor gardens, natural ventilation, and abundant daylight are becoming more common in offices, hospitals, and homes.

2. Social Connectivity

Spaces are no longer being designed solely for function — they are being shaped to foster community. Courtyards, communal kitchens, open-plan schools, and shared gardens encourage interaction and collective belonging. Mixed-use developments blend residential, commercial, and recreational spaces to create dynamic, walkable neighborhoods where people can live, work, and play in close proximity.

3. Sensory Experience and Comfort

Human-centric architecture goes beyond the visual. It considers sound, smell, texture, and even temperature to create comfort. Acoustic design reduces noise pollution, while materials are chosen for tactile warmth and familiarity. Lighting design mimics circadian rhythms, promoting better sleep and mental well-being. Thermal comfort, ergonomic spaces, and inclusive design ensure that environments serve people of all ages and abilities.

4. Mental Health and Mindfulness

Recognizing the global rise in stress and mental health challenges, architects are designing spaces that promote calm and introspection. Meditation rooms, quiet zones, and nature retreats are being integrated into public spaces and workplaces. Schools are including flexible classrooms and sensory rooms to support emotional regulation and focus in students.

5. Cultural and Emotional Meaning

A human-centric approach values local identity and cultural memory. Instead of imposing uniform international styles, architects are drawing from local materials, stories, and traditions. This creates a sense of belonging and emotional resonance. A well-designed space should not only shelter the body but also nourish the soul.

Technology as an Enabler, Not a Distraction

Interestingly, the return to human-centric design is not anti-technology — it’s about using technology to enhance, not replace, human experience. Smart systems adjust lighting and temperature based on occupancy and daylight. Data helps optimize air quality and energy use. Virtual reality is being used to involve users in the design process. The key is balance: technology should respond to human needs, not dominate them.

Examples of the Movement

Notable examples abound: The Maggie’s Centres in the UK provide beautifully designed spaces for cancer care that prioritize dignity and peace. The Bosco Verticale in Milan offers vertical forests that house both people and plants. Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay fuses technology and nature in a city park that is both functional and awe-inspiring.

The Future of Architecture is Human

As urbanization accelerates and climate challenges mount, the return of human-centric design is not just a trend — it’s a necessity. Architecture that cares for people, connects communities, and respects nature is becoming the blueprint for a healthier, more humane future.

In a world increasingly shaped by algorithms and automation, spaces that reflect the human spirit — our need for connection, beauty, safety, and meaning — are more vital than ever. The buildings of the future must not only stand tall but also stand for something: the well-being of those who inhabit them.

Friday, May 2, 2025

Freelance vs. Firm: Which Path Is Right for You in Architecture?

Freelance vs. Firm: Which Path Is Right for You in Architecture?

In architecture, career paths are as diverse as the designs we create.

One major crossroads every architect faces is this: Should I work for a firm, or build my career as a freelancer?

Both routes offer exciting opportunities — and unique challenges.

Choosing the right one depends on your personality, goals, and lifestyle.

Let's break down the key differences and help you decide which path might be right for you.

Life in an Architecture Firm

Working at a firm often provides structure, collaboration, and mentorship — ideal for learning and growing early in your career.

Advantages:

-

Mentorship & Team Learning: Working alongside experienced architects can dramatically accelerate your skills.

-

Resources & Big Projects: Firms often have access to large projects, cutting-edge software, and professional networks.

-

Job Stability: Salaries, benefits, and predictable hours (depending on the firm!) offer financial security.

-

Defined Roles: You'll likely specialize in certain tasks — drafting, client meetings, construction documents — building deep expertise.

Challenges:

-

Limited Creative Control: Designs are often shaped by senior architects or firm culture.

-

Office Politics: Like any corporate environment, navigating hierarchies and competition can be tough.

-

Work-Life Balance: Some firms expect long hours, especially before project deadlines.

Best for:

Those who thrive in team environments, value mentorship, and seek stability while developing a career foundation.

Life as a Freelance Architect

Freelancing offers independence, flexibility, and the chance to build your personal brand — but it's not for the faint-hearted.

Advantages:

-

Creative Freedom: You choose the projects, styles, and clients you want to work with.

-

Flexible Schedule: Work when and where you want — better work-life balance is possible.

-

Business Skills: You'll develop entrepreneurial abilities like marketing, client management, and financial planning.

-

Personal Brand Building: Your work and reputation are yours alone to grow.

Challenges:

-

Uncertain Income: Projects can be irregular, and slow periods require financial planning.

-

Self-Management: You handle everything — marketing, contracts, invoicing, taxes, and client communications.

-

Limited Resources: No built-in team or firm-provided software unless you invest yourself.

-

Networking Pressure: Finding and retaining clients is a constant part of the job.

Best for:

Those who are self-motivated, enjoy autonomy, and are willing to hustle for their own success.

Key Questions to Ask Yourself

To help you decide, reflect on these:

-

How comfortable am I with financial uncertainty?

-

Do I prefer working independently or collaborating within teams?

-

Am I ready to take on business and legal responsibilities?

-

How important is creative control to me?

-

Do I need a steady paycheck right now, or can I risk variability?

-

Am I willing to constantly market myself and network?

Can You Do Both?

Absolutely.

Many architects start in firms to build experience and a network, then transition to freelance work later.

Others freelance on the side while working part-time for a firm.

Some architects even create hybrid careers, combining consulting, teaching, and freelance design.

The important thing is to stay flexible and allow your career to evolve with your interests and goals.

Final Thoughts

In architecture, there is no one-size-fits-all career path.

Both firm life and freelancing offer rich, rewarding experiences — but in very different ways.

If you crave structure, teamwork, and steady growth, a firm might be your best fit.

If you seek creative freedom, autonomy, and entrepreneurial adventure, freelancing could be your calling.

Ultimately:

Choose the path that supports who you are today — and be brave enough to pivot as you grow.

Your architecture journey is your own masterpiece to design.

Thursday, May 1, 2025

Harbingers of Culture: A Comprehensive Guide to Designing Cultural Centers in Architecture

---------

Harbingers of Culture: A Comprehensive Guide to Designing Cultural Centers in Architecture

Understanding Cultural Identity:

Programming and Flexibility:

Spatial Planning and Layout:

Architectural Expression and Identity:

Integration of Technology:

Sustainability and Environmental Responsibility:

Community Engagement and Collaboration:

Conclusion:

------------

The sketches and basic renders I create are primarily intended to overcome creative blocks. They are abstract in nature and not final designs, often leaving room for multiple interpretations. For example, some sketches can be viewed both as elevations and floorplans, depending on how they are manipulated in space. These works are flexible and can be easily transformed by tweaking their geometry, adding modern facade systems, or incorporating other elements. An expert in the field can take these sketches, modify them, and further develop them into floorplans, sections, and elevations. Additionally, I also explore and publish my experiments with various AI image generators as part of my creative process.

I dedicate a significant amount of time each month to maintaining this blog—designing, publishing, and curating new content, including sketches and articles. This blog is entirely free and ad-free, and I plan to keep it that way. As I manage it independently, without any staff, your support truly makes a difference.

If this blog has helped streamline your work, sparked new ideas, or inspired your creativity, I kindly ask you to consider contributing to its ongoing upkeep through a donation. Your support enables me to continue providing high-quality, valuable content.

All sketches and artwork featured on this blog and my Pinterest pages are available for purchase or licensing, subject to my approval.

LINKEDIN PROFILE: https://www.linkedin.com/in/panagiotis-bozelos-96b896240

CV : https://drive.google.com/file/d/1mKd0tFYFREnN1mbsT0t42uOavFln4UOo/view?usp=sharing

BLOG: www.architectsketch.blogspot.com

PINTEREST (sketches): https://gr.pinterest.com/bozelos/sketches-and-plans/

Don't hessitate to communicate with me for anything you want.

Contact info:

bozpan13@gmail.com

bozpan@protonmail.com

TEL: 00306945176396

DONATE ME : Donate to Panagiotis Bozelos

---------------------------

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)